NETWORK CENTRIC WARFARE: UNDERSTANDING THE CONCEPT

Sections

Introduction

The Power of NCW

Self-Synchronization

“Power to the Edge” and “Agility”

Effects Based Operations (EBO) and NCW

The Entry Fee: High Quality Infostructure

Conceptual Understanding of NCW in the Indian Armed Forces

References

Introduction

In 21st Century warfare literature, the term “Network Centric Warfare/ Operations (NCW/ NCO)” is often used while discussing warfighting doctrines and transformational measures being taken towards modernising present-day militaries. However, there is often an inadequate understanding of this concept, as defined by the team of authors who originally proposed and developed it [1, 2 & 3]. Indeed, more often than not, the term is used synonymously with “networking”, whereas the concept is much deeper, and the connotations of acquiring net-centric capabilities pretty complex and far-reaching in nature. Here, an attempt is made to throw some light on the core concept of NCW as explained by its original authors.

After touching upon how “network” centric operations differ from “platform” centric operations leading to an increased Effective Engagement Envelope, the notions of “self-synchronisation” and “power to the edge”, which fall under the umbrella concept of NCW, are discussed. Thereafter, the related concept of “Effects based Operations (EBO)” is briefly discussed. Finally, it is emphasized that robust networking is only the “entry fee” (and not the end-result) of operationalising the NCW concept.

The Power of NCW

In pure computational terms, NCW draws its strength from Metcalf’s law, which asserts that the power of a network is proportional to the square of the number of nodes in the network. The manner in which this translates in practical terms into increased combat power in military scenarios is given out in succeeding paragraphs.

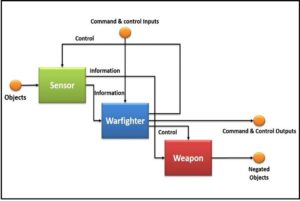

The source of increased combat power associated with NCO lies in the combat power of “platforms” or “nodes” operating in a stand-alone mode. In order to successfully engage a target, the target must be detected, identified, decision made to engage the target and the weapon aimed and fired. Associated with a particular engagement is a time budget and engagement range. The consumption of time depends upon effective ranges of the sensors and weapons, their kill radius, time required to communicate and process information and decision-making time [2].

The effective range depends upon both the range characteristics of the sensors and weapons, as well as the effect of range on the consumption of time. The figure below portrays an engagement by a Platform Centric Shooter, where sensing and engagement capabilities reside on the same platform and there is only limited capability for a weapons platform to engage a target based on awareness generated by other platforms. This figure describes the functional components of an engagement for a single warfighter on the ground, in a tank, flying an aircraft or commanding a surface or subsurface naval combatant platform.

Platform-Centric Shooter

Platform-Centric Engagement Envelope

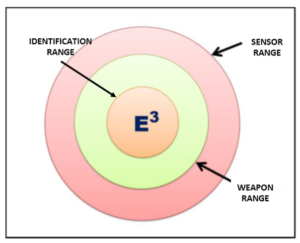

In platform centric engagement, ie, when the sensor, decision maker and shooter are all on the same platform, the Effective Engagement Envelope, or E3, is the area defined by the overlap of engagement quality awareness and the weapons maximum employment envelope (Please see the figure below). The instantaneous combat power for a platform-centric engagement is proportional to the Effective Engagement Envelope. As is apparent from the diagram, in platform-centric operations combat power is often marginalized by the inability of the platform to generate engagement quality awareness at ranges greater than or equal to the maximum weapons employment envelope, thus limiting the effective engagement range to less than its weapon range. For example, in the case of a non-networked fighter aircraft, this range would be limited to the visual identification range of the pilot, which may be as low as 2-3 kms, while the weapon range would be typically much higher (25-30 kms).

Platform Centric Engagement Envelope

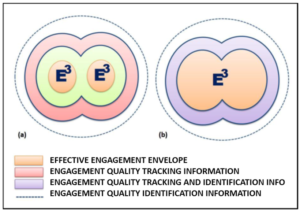

Non-Networked Sensors and Shooters

Figure (a) below compares a case that portrays two platform-centric shooters operating in close proximity, supported by an external sensing capability that can provide identification information (such as an AWACS, range depicted by the dashed circle), but these are not networked, thus not facilitating real-time sharing of information. In this operational situation, real-time engagement information (sensing plus identification) cannot be shared effectively and combat power is not maximized.

NCW Value Added Combat Power

Network Centric Operation

In contrast, Figure (b) portrays the value-added combat power associated with a network-centric operation. In this mode of operation, near real-time information sharing among nodes enables potential combat power to be increased. The robust networking of sensors (AWACS and aircraft radars) provides the force with the capability to generate engagement quality shared awareness. The overlap of this increased awareness zone with the weapons ranges gives the increased Effective Engagement Envelope. The potential increase in total combat power associated with a network-centric operation is represented by the increased area of the Effective Engagement Envelope. This simple example illustrates the application of Metcalfe’s Law to military operations.

Self-Synchronization

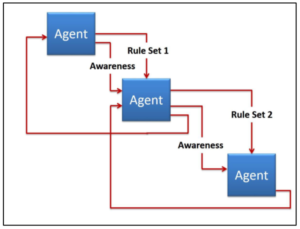

Self-synchronization is perhaps the ultimate in achieving increased tempo and responsiveness. Self-synchronization is a mode of interaction between two or more entities. The figure below portrays the key elements of self-synchronization: two or more robustly networked entities (agents), shared awareness, a rule set (rules or guidelines for operation) and a value-adding interaction. The combination of a rule set and shared awareness enables the entities to operate in the absence of traditional hierarchical mechanisms for command and control. The rule set describes the desired outcome (eg, commander’s intent and rules of engagement) in various operational situations.

Self Synchronized Interaction

Self-synchronisation may be used to advantage when, for instance, a group of fighter aircraft engages enemy aircraft. Achieving coordination amongst combat groups from different formations in a projection area battle would be another example. An area where the application of self-synchronization has significant potential is a class of warfighting activities providing supporting services, such as logistics, fire support, and close air support. In platform-centric operations, the supported agent typically requests support, often via voice. Self-synchronization provides a mechanism for making combat processes time-efficient.

“Power to the Edge” and “Agility”

Alberts and Hayes explained the idea of the inherent benefits of sharing information in a networked environment in their book titled, Power to the Edge: Command Control in the Information Age [4]. The book argues that current command and control relationships, organizations and systems are just not up to the task of executing warfare in the Information Age.

It is critical to push essential decision making information out to the “edges” of the organization. “Power to the Edge” is about changing the way individuals and organizations relate to one another and work. It involves the empowerment of individuals at the edge of an organiza¬tion (where the organization interacts with its operating environment to have an impact on that environment) which, in the case of military organizations, would translate to the tactical domain.

The concept of “Power to the Edge” is an extension of NCW, where the ubiquitous nature of IT through robust networking makes the application of this concept in military organizations feasible. The transition from strictly hierarchical organizational structures to flatter ones needs to be hastened in order to reap the full benefits of NCW. The power of the network has provided new and innovative approaches to command and con¬trol of organizations. Such responsive organisations are also expected to lead to greater “agility” in reacting to complex, Fourth Generation type of warfighting scenarios.

Effects Based Operations (EBO) and NCW

Throughout history, decision-makers have sought to create conditions that would achieve their objectives and policy goals. Edward Smith gives a straightforward definition of EBO, as under [5]:-

“Effects-based operations are coordinated sets of actions directed at shaping the behavior of friends, foes, and neutrals in peace, crisis, and war.”

The objective of an effects-based strategy is not to win a military campaign or a war through the physical attrition of the enemy but to induce an opponent to pursue a course of action consistent with own security interests.

The question of will is fundamental to both the symmetric and asymmetric models of conflict but in different ways. In a symmetric, attrition-based conflict, the destruction of the enemy’s physical capacity to wage war is the objective. In an asymmetric conflict, the destruction is aimed at creating the desired psychological or cognitive effect.

EBO is primarily about focusing knowledge, precision, speed and agility on the enemy decision makers to degrade their ability to take coherent action rather than conducting combat operations for more efficient destruction of the enemy. The knowledge, precision, speed and agility brought about by NCO provide the necessary ingredients for EBO.

In summary, the combination of network-centric capabilities and an effects-based approach provides commanders and planners with a new potential for attacking the elements of the enemy’s will directly, thereby avoiding, or at least diminishing, reliance on sheer physical destruction.

The Entry Fee: High Quality Infostructure

The essential pre-requisite or entry fee for NCW is an infostructure that provides all elements of the warfighting enterprise with access to high-quality information services. This infostructure is required to deliver different qualities of service for different requirements. For example, target engagement requires high data rates and low latencies, tactical command and control can tolerate delays of the order of seconds, while logistics requirements are not very time sensitive.

Further, there is the need for a high level of integration of computing elements and communications into a single infostructure, catering for reliability and security needs for different types of operational requirements.

Finally, it is once again highlighted that such an infostructure is only an enabler, and not an end-result, towards achieving net-centric capabilities.

Conceptual Understanding of NCW in the Indian Armed Forces

The Indian Army (IA) Doctrine of 2004 had stated that Network Centric Warfare is a new method of warfighting enabled by the ongoing (system-of-systems) RMA, which itself is contingent upon robust and sophisticated C4I2SR systems. The doctrine notes that RMA concepts can have a dramatic effect on the conduct of warfare in a conventional (second and third generation warfare) scenario and, to a lesser extent, even in a Low Intensity Conflict (akin to 4GW) scenario. The IA Doctrine of 2010, on the other hand, while dropping the RMA terminology, endorses the concept of NCW.

Beyond the above doctrinal references, there is very limited formal treatment on the NCW/ NCO warfighting paradigms within the Indian Armed Forces. It would not be unfair to state that, in most quarters, NCW is indeed understood as a synonym for robust networking, and that concepts such as “self-synchronization” and “power to the edge” are rarely discussed, if at all. There is another terminology in vogue for more than a decade now, namely, “network-enabled” as opposed to “network-centric”. A distinction between these terms, however, does not appear to exist in any formal literature.

There seems to be a clear need, therefore, of going beyond mere doctrinal mentions, and making the necessary efforts to understand this concept at a deeper level, analyze its applicability in the Indian context, and chart out a road-map for operationalizing NCW as most suited to the Indian security scenario.

References

(1) Cebrowski A K, The Implementation of Network Centric Warfare, Office of Force Transformation, US DoD, 05 Jan 05, Accessed 28 Aug 2020, https://apps.dtic.mil/dtic/tr/fulltext/u2/a446831.pdf.

(2) Alberts DS, Garstka JJ, and Stein FP, Network Centric Warfare: Developing and Leveraging Information Superiority, 2nd edition (revised). Washington, DC, DoD CCRP, Feb 2000, Accessed 28 Aug 2020, http://dodccrp.org/files/Alberts_NCW.pdf.

(3) Alberts DS, Garstka JJ, Hayes RE, and Signori DA, Understanding Information Age Warfare, Washington, DC, DoD CCRP, 2001, Accessed 28 Aug 2020, http://www.dodccrp.org/files/Alberts_UIAW.pdf.

(4) Edward A Smith Jr, Effects-Based Operations: Applying Network-Centric Warfare in Peace, Crisis and War, Washington, DC, DoD CCRP, 2002, Accessed 28 Aug 2020, http://www.dodccrp.org/files/Smith_EBO.pdf.

(5) Alberts, DS and Hayes, RE, Power to the Edge: Command … Control … in the Information Age, Washington, DC, DoD CCRP, 2003, Accessed 28 Aug 2020, http://www.dodccrp.org/files/Alberts_Power.pdf.

0 Comments