NETWORK CENTRIC WARFARE: A COMMAND & CONTROL CONCEPT

Sections

Introduction

The OODA Loop

“System of Systems” RMA

“System of Systems” RMA vis-a-vis the OODA Loop

NCW vis-a-vis the “System of Systems” RMA

Self-Synchronisation

Power to the Edge

Complexity and Agility

Effects Based Operations (EBO)

References

Introduction

Two earlier posts on Network Centric Warfare (NCW), Origins and Main Characteristics and Understanding the Concept, give an overview of what the NCW concept is all about. While networks and information management are central to this concept, it is important to emphasize that NCW is essentially a Command & Control concept. This post endeavours to highlight this aspect.

In the two posts referred to above, it was brought out that the genesis of the NCW concept lies in Admiral Owen’s theory of the current “System of Systems” Revolution in Military Affairs (RMA), and that these concepts have linkages with Col John Boyd’s Observe-Orient-Decide-Act (OODA) Loop Model. Further, flowing out of the NCW concept are the notions of Self-Synchronisation of forces, “Power to the Edge”, Effects Based Operations (EBO) and the concept of Agility. All of these are various facets of how command & control is effected on the battlefield. In this write-up, these ideas are stitched together and elaborated upon further.

The OODA Loop

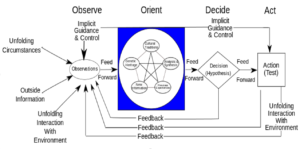

The military strategist Col John Boyd of the US Air Force developed the OODA Loop model based on his experiences as a fighter pilot during the Korean War and later as an instructor. The model captures a decision making process which consists of the Observe, Orient, Decide and Act phases. It is a cyclical model, using which one is able to continuously adapt to changing circumstances and use this to draw on one’s strengths. By responding quickly to situations and taking appropriate decisions, one can get ahead of one’s opponents [1].

The OODA Loop Model

The OODA loop bases itself on the premise that parties to a conflict or competitors are systems that operate through a rational cyclical decision-making process, as under:-

- Observe. The system scans the environment and gathers information regarding changes in the environment that affects the system directly or indirectly.

- Orient. Orientation is interpretation of the observed information, or converting information into knowledge by developing concepts through analysis of information. The way the system interprets knowledge depends on culture, genetic heritage, ability to analyze and synthesize, experience, and latest changes to information, and success depends on such interpretation being better or more relevant than that of the competitors.

- Decide. Decide is weighing the several options or alternatives available from the knowledge body generated during the orientation phase, and picking the best one.

- Act. Act is carrying out or implementing the selected decision. This completes the OODA Loop, and the feedback of the implementation is the basis for the next round of observation.

“System of Systems” RMA

The “Current RMA” is often viewed as “a military revolution combining technical advances in surveillance, Command, Control Communication, Computers and Intelligence (C4I) and precision munitions with new operational concepts, including Information Warfare, continuous and rapid joint operations and holding the entire theatre at risk.”

Admiral William A Owens of the US Navy and later Vice Chairman of Joint Chiefs of Staff, US, was an advocate of the “system of systems” RMA approach, in which an all-encompassing and all-knowing technological system manned by commanders can deploy subsystems of force and “see” all the assets and vulnerabilities of the enemy. As per Admiral Owens, the changes heralding this current RMA fall into three categories, as under [2]:-

- Intelligence, Surveillance and Reconnaissance (ISR). The elements of ISR include sophisticated radar monitoring, satellite surveillance and reconnaissance, unmanned aircraft with advanced radars and video cameras, airborne and land-based sensors and expensive aircraft with advanced surveillance capabilities.

- C4I. C4I elements include both forward and rear command and control technologies, secure communications and computer processing that ranges from laptops and handheld computers in the field to immense supercomputers, and everything in between. An increasingly important element of C4I is the GPS. It also includes computerized “battle management systems” designed to aggregate data about a combat operation and present it to commanders in a form that is helpful for planning and execution.

- Precision Guided Munitions (PGMs). PGMs include cruise missiles such as Tomahawk, launched from ships and aircraft; “smart” bombs such as laser-guided bomb or bombs guided by GPS; a wide range of guided missiles such as laser-guided, air-to-ground antitank missile; ground-fired, man-portable missile systems such as “fire and forget” antitank missile guided by a heat-seeking warhead that locks onto an infrared signature acquired by the operator and others with “smart” capabilities using one or more technologies such as anti-radiation, heat-seeking and terrain-mapping, among others; and the use of unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) armed with missiles that can be targeted using radar or video cameras on-board the drone.

These broad system architectures and joint operational concepts lead to the creation of a new system-of-systems. This new system-of-systems capability, combined with joint doctrine designed to take full advantage of these new fighting capabilities, is at the heart of the current RMA.

“System of Systems” RMA vis-à-vis the OODA Loop

There is a clear correlation between the “system of systems” concept and Colonel James Boyd’s OODA Loop. The “ISR” corresponds to the “Observe” part, the “C4I” to the “Orient-Decide” part and the “Precision Systems” to the “Act” part of the Loop. Such a system capability gives rise to real time awareness of the status of own forces, as well as the understanding of what they can do with their growing capacity to apply force with speed, accuracy and precision. Thus, the right force can be matched to the most promising course of action at both the tactical and operational levels of warfare. Further, tailored forces can be applied faster, with more precise weapons and over greater distances. Advances in ISR allow more accurate post-damage assessment. This battle assessment, in turn, makes subsequent actions more effective. As a result, it is possible to operate within the opponent’s decision cycle. Thus, the current RMA is essentially about leveraging networking and information processing technologies to provide a quantum improvement in command & control capabilities on the field.

NCW vis-à-vis the “System of Systems” RMA

As per Cebrowski NCW, as an organizing principle, accelerates our ability to know, decide, and act by linking sensors, communications systems, and weapons systems in an interconnected grid [3, 4]. Alberts, who along with his team was the first to present NCW as a formal concept, states that the enabling elements are a high performance information grid, access to all appropriate information sources, weapons reach and manoeuvre with precision and speed of response, value-adding C2 processes – to include high-speed automated assignment of resources to need – and integrated sensor grids closely coupled in time to shooters and C2 processes [5]. The underlying OODA Loop is evident in both these ideas.

Flowing from the above, a direct co-relationship may be drawn between the three essential components of NCW, ie, sensors, decision-makers and shooters, with the three constituents of Admiral Owen’s “systems of systems” concept of Current RMA, namely, ISR, C4I and PGMs. Indeed, insofar as the shortening of the OODA loop enabling functioning within the decision cycle of the enemy is concerned, the “NCW” and “Current RMA” refer to more or less the same, if not identical, concepts [6].

NCW vis-à-vis Current “System of Systems” RMA

However, there is much more to the NCW concept than merely the speeding up of the OODA Loop. NCW is principally a command and control theory of warfare, involving concepts such as Self-Synchronisation of forces, Power to the Edge, and Agility. These are further discussed in succeeding paragraphs.

Self-Synchronization

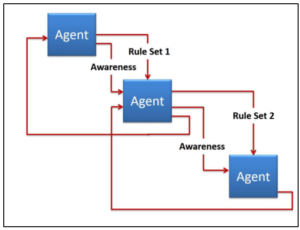

Self-synchronization is a mode of interaction between two or more peer entities. The figure below portrays the key elements of self-synchronization: two or more robustly networked entities, shared awareness, a rule set (rules or guidelines for operation) and a value-adding interaction. The combination of a rule set and shared awareness enables the entities to operate in the absence of traditional hierarchical mechanisms for command and control. The rule set describes the desired outcome (eg, commander’s intent) in various operational situations [3].

Self-Synchronization Interaction

As an example, during a fast moving projection area battle in mechanised operations, combat teams/ groups and even combat commands belonging to different formations can achieve much higher combat effectiveness through peer coordination (based on established engagement protocols/ rule-sets), rather that receiving instructions from their respective hierarchies. However, this would only be feasible if there is a common operating picture and the higher commander’s intent is clearly known to all participating entities. Another area where the application of self-synchronization has significant potential is a class of warfighting activities providing supporting services, such as logistics, fire support, and close air support. In platform-centric operations, the supported agent typically requests support, often via voice. Significant time is often spent communicating position information. Self-synchronization provides a mechanism for pushing logistics in anticipation of need.

Power to the Edge

Alberts and Hayes explained the idea of the inherent benefits of sharing information in a networked environment in their book titled, Power to the Edge: Command Control in the Information Age. The book argues that current command and control relationships, organizations and systems are just not up to the task of executing warfare in the Information Age [7].

It is critical to push essential decision making information out to the “edges” of the organization. “Power to the Edge” is about changing the way individuals and organizations relate to one another and work. It involves the empowerment of individuals at the edge of an organization (where the organization interacts with its operating environment to have an impact on that environment) which, in the case of military organizations, would translate to the tactical domain.

“Power to the Edge” is an extension of NCW and the concept of self-synchronisation of forces, where the ubiquitous nature of IT through robust networking makes the vision of applying this concept in military organizations too. The transition from strictly hierarchical organizational structures to flatter ones needs to be hastened in order to reap the full benefits of NCW. This would involve taking advantage of more powerful networks to push information and thus greater situational awareness to all elements on the battlefield. The power of the network has provided new and innovative approaches to command and control of organizations.

Complexity and Agility

National security in the “Information Age” involves a complex environment, where any armed force is confronted by instantaneous media coverage, insurgencies, terrorist cells, regional instability and adversaries, using commercially available state-of-the-art high technology devices. Therefore, military operations are now characterized by greater complexity. Events involving greater complexity are less effectively controlled through traditional industrial-age methods that de-construct problems into a manageable series of predictable pieces and better addressed by achieving “agility” attained as a result of net-centricity through flatter organisations and self-synchronisation amongst combat elements [8].

Effects Based Operations (EBO)

Throughout history, decision-makers have sought to create conditions that would achieve their objectives and policy goals. Military commanders and planners have tried to plan and execute campaigns to create such favourable conditions – an approach that would be considered “effects-based” in today’s terminology. EBO is a way of thinking or a methodology for planning, executing and assessing operations designed to attain specific effects that are required to achieve desired national security outcomes [4].

Edward Smith gives a straightforward definition of EBO, as under [9]:-

“Effects-based operations are coordinated sets of actions directed at shaping the behavior of friends, foes, and neutrals in peace, crisis, and war.”

The EBO methodology is a refinement or evolution of the objectives-based planning methodology that can be incorporated into the military doctrine of any country. Commanders and planners can apply the EBO methodology to all operations, ranging from peacetime engagement and stability operations to combating terrorism and major combat operations.

EBO is not simply a mode of warfare at the tactical level, nor is it purely military in nature. EBO encompasses the full range of political, military and economic actions a nation might take to shape the behaviour of an enemy, of a would-be opponent, and even of allies and coalition partners. These actions may include the destruction of an enemy’s forces and capabilities. However, the objective of an effects-based strategy, including the actions that advance it, is not to win a military campaign or a war through the physical attrition of the enemy but to induce an opponent or an ally or a neutral to pursue a course of action consistent with our security interests.

The question of will is fundamental to both the symmetric and asymmetric models of conflict but in different ways. In a symmetric, attrition-based conflict, the destruction of the enemy’s physical capacity to wage war is the objective. In an asymmetric conflict, the destruction is aimed at creating the desired psychological or cognitive effect.

In the asymmetric, essentially effects-based contest, the objective is to break the will or otherwise shape the behaviour of the enemy so that he no longer retains the will to fight, or to so disorient him that he can no longer fight or react coherently. Although physical destruction remains a factor in EBO, it is the creation of such a psychological or cognitive effect that is the primary focus of the effects-based approach.

EBO is primarily about focusing knowledge, precision, speed and agility on the enemy decision makers to degrade their ability to take coherent action rather than conducting combat operations or more efficient destruction of the enemy. In other words, the aim is to disrupt the OODA Loop of the enemy to such an extent that he is completely disoriented and unable to function effectively. The knowledge, precision, speed and agility brought about by NCO provide the necessary ingredients for EBO. In this context, the following quote from Sun Tzu’s The Art of War is relevant:-

“For to win one hundred victories in one hundred battles is not the acme of skill. To subdue the enemy without fighting is the acme of skill.”

In summary, the combination of network-centric capabilities and an effects-based approach provides commanders and planners with a new potential for attacking the elements of the enemy’s will directly, thereby avoiding, or at least diminishing, our reliance on sheer physical destruction.

Conclusion

This post has attempted to highlight the fact that NCW is essentially a command & control concept. In addition to directly contributing towards increased combat effectiveness by providing efficient interfaces amongst the sensors, shooters and decision makers, it also opens up the feasibility of implementing flatter organisational structures and peer-to-peer command & Control protocols, which would make military organisations more effective in conventional battlefield scenarios, as well as more “agile” in dealing dealing with the complexities of hybrid warfare on the 21st Century battlespace.

References

(1) Nule, Lt Col Jeffrey N, A Symbiotic Relationship: The OODA Loop, Intuition, and Strategic Thought, US Army War College, Mar 2013.

(2) Owens, Admiral W, Emerging System of Systems, Military Review, Vol 75 No 3, May-June 1995.

(3) Cebrowski AK and Garstka John, Network-Centric Warfare: Its Origin and Future, US Naval Institute Proceedings, Annapolis, Maryland, January 1998.

(4) Cebrowski A K, The Implementation of Network Centric Warfare, Office of Force Transformation, US DoD, Washington, D C, 05 Jan 2005, pp. 15-21.

(5) Alberts DS, Garstka JJ, and Stein FP, Network Centric Warfare: Developing and Leveraging Information Superiority, 2nd edition (revised). Washington, DC, DoD CCRP, Feb 2000.

(6) Network Centric Warfare – Concept, Status and Way Forward for the Indian Army [Restricted], Flash Perspectives, Military College of Telecommunication Engineering, Dec 2015, pp. 24.

(7) Alberts, DS and Hayes, RE, Power to the Edge: Command … Control … in the Information Age, Washington, DC, DoD CCRP, 2003.

(8) Albers, David S, The Agility Advantage, Command and Control Research Program, US DoD, Sep 2011.

(9) Edward A Smith Jr, Effects-Based Operations: Applying Network-Centric Warfare in Peace, Crisis and War, Washington, DC, DoD CCRP, 2002.

0 Comments