ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE IN MILITARY OPERATIONS: AN OVERVIEW - PART I

Sections

Introduction

AI – Current Status of Technology

AI in Military Operations

LAWS – Legal and Ethical Issues

References

Introduction

Artificial Intelligence (AI) has become a field of intense interest and high expectations within the defence technology community. AI technologies hold great promise for facilitating military decisions, minimizing human causalities and enhancing the combat potential of forces, and in the process dramatically changing, if not revolutionizing, the design of military systems. This is especially true in a wartime environment, when data availability is high, decision periods are short, and decision effectiveness is an absolute necessity.

The rise in the use of increasingly autonomous unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) in military settings has been accompanied by a heated debate as to whether there should be an outright ban on Lethal Autonomous Weapon Systems (LAWS), sometimes referred to as ‘killer robots’. Such AI enabled robots, which could be in the air, on the ground, or under water, would theoretically be capable of executing missions on their own. The debate concerns whether artificially intelligent machines should be allowed to execute such military missions, especially in scenarios where human lives are at stake.

This two-part article focuses on development and fielding of LAWS against the backdrop of rapid advances in the field of AI, and its relevance to the Indian security scenario. This first part reviews the status of AI technology, gives a broad overview of the possible military applications of this technology and brings out the main legal and ethical issues involved in the current ongoing debate on development of LAWS.

AI – Current Status of Technology

AI – A Maturing Technology

A general definition of AI is the capability of a computer system to perform tasks that normally require human intelligence, such as visual perception, speech recognition and decision-making. Functionally, AI enabled machines should have the capability to learn, reason, judge, predict, infer and initiate action. In layman’s terms, AI implies trying to emulate the brain. There are three main ingredients that are necessary for simulating intelligence: the brain, the body, and the mind. The brain consists of the software algorithms which work on available data, the body is the hardware and the mind is the computing power that runs the algorithms. Technological breakthroughs and convergence in these areas is enabling the AI field to rapidly mature.

AI, Machine Learning and Deep Learning

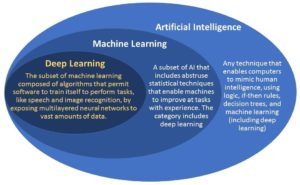

Last year, in a significant development, Google DeepMind’s AlphaGo program defeated South Korean Master Lee Se-dol in the popular board game Go, and the terms AI, Machine Learning, and Deep Learning were used to describe how DeepMind won. The easiest way to think of their inter-relationship is to visualize them as concentric circles, with AI the largest, then Machine Learning, and finally Deep Learning – which is driving today’s AI explosion – fitting inside both [1]. AI is any technique that enables computers to mimic human intelligence. Machine Learning is a subset of AI, which focuses on the development of computer programs that can change when exposed to new data, by searching through data to look for patterns and adjusting program actions accordingly. Deep Learning is a further subset of Machine Learning that is composed of algorithms which permit software to train itself by exposing multi-layered neural networks (which are designed on concepts borrowed from a study of the neurological structure of the brain) to vast amounts of data.

AI Technologies

The most significant technologies which are making rapid progress today are natural language processing and generation, speech recognition, text analytics, machine learning and deep learning platforms, decision management, biometrics and robotic process automation. Some of the major players in this space are: Google, now famous for its artificial neural network based AlphaGo program; Facebook, which has recently announced several new algorithms; IBM, known for Watson, which is a cognitive system that leverages machine learning to derive insights from data; Microsoft, which helps developers to build Android, iOS and Windows apps using powerful intelligence algorithms; Toyota, which has a major focus on automotive autonomy (driver-less cars); and Baidu Research, the Chinese firm which brings together global research talent to work on AI technologies.

AI – Future Prospects

Today, while AI is most commonly cited for image recognition, natural language processing and voice recognition, this is just an early manifestation of its full potential. The next step will be the ability to reason, and in fact reach a level where an AI system is functionally indistinguishable from a human. With such a capability, AI based systems would potentially have an infinite number of applications [2].

The Turing Test

In a 1951 paper, Alan Turing proposed the Turing Test to test for artificial intelligence. It envisages two contestants consisting of a human and a machine, with a judge, suitably screened from them, tasked with deciding which of the two is talking to him. While there have been two well-known computer programs claiming to have cleared the Turing Test, the reality is that no AI system has been able to pass it since it was introduced. Turing himself thought that by the year 2000 computer systems would be able to pass the test with flying colours! While there is much disagreement as to when a computer will actually pass the Turing Test, one thing all AI scientists generally agree on is that it is very likely to happen in our lifetime [3].

Fear of AI

There is a growing fear that machines with artificial intelligence will get so smart that they will take over and end civilization. This belief is probably rooted in the fact that most of society does not have an adequate understanding of this technology. AI is less feared in engineering circles because there is a slightly more hands-on understanding of the technology. There is perhaps a potential for AI to be abused in the future, but that is a possibility with any technology. Apprehensions about AI leading to end-of-civilisation scenarios are perhaps largely based on fear of the unknown, and appear to be largely unfounded.

AI in Military Operations

AI – Harbinger of a New RMA?

Robotic systems are now widely present in the modern battlefield. Increasing levels of autonomy are being seen in systems which are already fielded or are under development, ranging from systems capable of autonomously performing their own search, detect, evaluation, track, engage and kill assessment functions, fire-and-forget munitions, loitering torpedoes, and intelligent anti-submarine or anti-tank mines, among numerous other examples. In view of these developments, many now consider AI & Robotics technologies as having the potential to trigger a new RMA, especially as Lethal Autonomous Weapon Systems (LAWS) continue to achieve increasing levels of sophistication and capability.

“LAWS” – Eluding Precise Definition

In the acronym “LAWS”, there is a fair amount of ambiguity in the usage of the term “autonomous”, and there is lack of consensus on how a “fully autonomous” weapon system should be characterised. In this context, two definitions merit mention, as under:-

- US DoD Definition. A 2012 US Department of Defense (DoD) directive defines an autonomous weapon system as one that “once activated, can select and engage targets without further intervention by a human operator.” More significantly, it defines a semi-autonomous weapon system as one that, “once activated, is intended to engage individual targets or specific target groups that have been selected by a human operator”. By this yardstick, a weapon system, once programmed by a human to destroy a “target group” (which could well be interpreted to be an entire army) and thereafter seeks and destroys individual targets autonomously, would still be classified as semi-autonomous [4]!

- Human Rights Watch (HRW) Definition. As per HRW, “fully autonomous weapons are those that once initiated, will be able to operate without Meaningful Human Control (MHC). They will be able to select and engage targets on their own, rather than requiring a human to make targeting and kill decisions for each individual attack.” However, in the absence of consensus on how MHC is to be specified, it concedes that there is lack of clarity on the definition of LAWS [5].

Narrow AI – An Evolutionary Approach

There is a view that rather than focus autonomous systems alone, there is a need to leverage the power of AI for increasing the combat power of the current force. This approach is referred to as “Narrow” or “Weak” AI. Narrow AI could lead to many benefits, as follows: using image recognition from video feeds to identify imminent threats, anticipating supply bottlenecks, automating administrative functions, etc. Such applications would permit force re-structuring, with smaller staff comprising of data scientists replacing large organizations. Narrow AI thus has the potential to help the Defence Forces improve their teeth-to-tail ratio [6].

Centaur: Human-Machine Teaming

Another focus area on the evolutionary route to the development of autonomous weapons is what can be termed as “human-machine teaming,” wherein machines and humans work together in a symbiotic relationship. Like the mythical centaur, this approach envisages harnessing inhuman speed and power to human judgment, combining machine precision and reliability with human robustness and flexibility, as also enabling computers and humans helping each other to think, termed as “cognitive teaming.” Some functions will necessarily have to be completely automated, like missile defense lasers or cybersecurity, and in all such cases where there is no time for human intervention. But, at least in the medium term, most military AI applications are likely to be team-work: computers will fly the missiles, aim the lasers, jam the signals, read the sensors, and pull all the data together over a network, putting it into an intuitive interface, using which humans, using their experience, can take well informed decisions [7].

LAWS – Legal and Ethical Issues

LAWS powered by AI are currently the subject of much debate based on ethical and legal concerns, with human rights proponents recommending that development of such weapons should be banned, as they would not be in line with international humanitarian laws (IHL) under the Geneva Convention. The legal debate over LAWS revolves around three fundamental issues, as under:-

- Principle of “Distinction.” This principle requires parties to an armed conflict to distinguish civilian populations and assets from military assets, and to target only the latter (Article 51(4)(b) of Additional Protocol I).

- Principle of “Proportionality”. The law of proportionality requires parties to a conflict to determine the civilian cost of achieving a particular military target and prohibits an attack if the civilian harm exceeds the military advantage (Articles 51(5)(b) and 57(2)(iii) of Additional Protocol I).

- Legal Review. The rule on legal review provides that signatories to the Convention are obliged to determine whether or not new weapons as well as means and methods of warfare are in adherence to the Convention or any other international law (Article 36 of Additional Protocol I).

Marten’s Clause

It has also been argued that fully autonomous weapon systems do not pass muster under the Marten’s Clause, which requires that “in cases not covered by the law in force, the human person remains under the protection of the principles of humanity and the dictates of the public conscience” (Preamble to Additional Protocol I) [8].

“Campaign to Stop Killer Robots”

Under this banner, Human Rights Watch (HRW) has argued that fully autonomous weapon systems would be prima facie illegal as they would never be able to adhere to the above provisions of IHL, since such adherence requires a subjective judgement, which machines can never achieve. Hence, their development should be banned at this stage itself [9].

Counter-Views

There is an equally vocal body of opinion which states that development and deployment of LAWS would not be illegal, and in fact would lead to saving of human lives. Some of their views are listed as under [10]:-

- LAWS do not need to have self-preservation as a foremost drive, and hence can be used in a self-sacrificing manner, saving human lives in the process.

- They can be designed without emotions that normally cloud human judgment during battle leading to unnecessary loss of lives.

- When working as a team with human soldiers, autonomous systems have the potential capability of objectively monitoring ethical behaviour on the battlefield by all parties.

- The eventual development of robotic sensors superior to human capabilities would enable robotic systems to pierce the fog of war, leading to better informed “kill” decisions.

- Autonomous weapons would have a wide range of uses in scenarios where civilian loss would be minimal or non-existent, such as naval warfare.

- The question of legality depends on how these weapons are used, not their development or existence.

- It is too early to argue over the legal issues surrounding autonomous weapons because the technology itself has not been completely developed yet.

Degree of Autonomy and Meaningful Human Control (MHC)

Central to the issues being debated are the aspects of degree of autonomy and MHC. LAWS have been broadly classified into three categories: “Human-in-the-Loop” LAWS can select targets, while humans take the “kill” decision; “Human-on-the-Loop” weapons can select as well as take “kill” decisions autonomously, while a human may override the decision by exerting oversight; and “Human-out-of-the-Loop” LAWS are those that may select and engage targets without any human interaction. Entwined within this categorisation is the concept of MHC, ie, the degree of human control which would pass muster under IHC. Despite extensive discussions at many levels, there is no consensus so far on what is meant by full autonomy as also how MHC should be defined [11,12].

Deliberations at the UN

Triggered by the initiatives of HRW and other NGOs, deliberations have been going on under the aegis of UN Convention on Certain Conventional Weapons (CCW) with the aim of determining whether or not banning the development of LAWS is warranted. After three years of deliberations amongst informal group of experts between 2013 and 2016, it was decided in Dec 2016 that now a Group of Government Experts (GGE) will consider the issue later this year, under the chairmanship of the Indian Permanent Representative to the UN, Ambassador Amandeep Singh Gill, giving India an opportunity to play a significant role in shaping these deliberations.

This discussion is taken forward in Part II of this write-up, which focusses on international and Indian perspectives on the current status and future prospects for development and deployment of LAWS.

References

(1) Michael Copeland, What’s the Difference between Artificial Intelligence, Machine Learning, and Deep Learning?, July 29, 2016, NVIDIA, Accessed 15 Nov 2020.

(2) Christina Cardoza, What is the Current State of AI?, 30 Sep 2016, SD Times, Accessed 15 Nov 2020.

(3) Margaret Grouse, Turing Test, Tech Target, Accessed 15 Nov 2020.

(4) Ashton B Carter, Autonomy in Weapon Systems, US Depart of Defence Directive 3000.09, 21 Nov 2012, Accessed 15 Nov 2020.

(5) Mary Wareham, Presentation on Campaign to Stop Killer Robots, PIR Centre Conference on Emerging Technologies, Moscow, 29 Sep 2016, Accessed 15 Nov 2020.

(6) Benjamin Jensen and Ryan Kendall, Waze for War: How the Army can Integrate Artificial Intelligence, 02 Sep 2106, War On The Rocks, Accessed 15 Nov 2020.

(7) Sydney J Freedberg Jr, Centaur Army: Bob Work, Robotics, & The Third Offset Strategy, 09 Nov 2015, Breaking Defence, Accessed 15 Nov 2020.

(8) Protocol Additional to the Geneva Conventions of 12 August 1949, and relating to the Protection of Victims of International Armed Conflicts (Protocol I), 08 Jun 1977, Accessed 15 Nov 2020.

(9) International Human Rights Clinic, Losing Humanity: The Case against Killer Robots, Human Rights Watch, Nov 2012, Accessed 15 Nov 2020.

(10) Ronald Arkin, Counterpoint, Communications of the ACM, December 2015, Accessed 15 Nov 2020.

(11) Noel Sharkey, Towards a Principle for the Human Supervisory Control of Robot Weapons, Politica & Società, Number 2, May-August 2014, Accessed 15 Nov 2020.

(12) Kevin Neslage, Does ‘Meaningful Human Control’ Have Potential for the Regulation of Autonomous Weapon Systems? University of Miami National Security and Armed Conflict Review, 2015-16, Accessed 15 Nov 2020.

0 Comments